Five minute read

Clare Montagu, Poppy’s CEO, explains how the Fuller Inquiry could be an opportunity to challenge a culture of secrecy within mortuary care.

In July 2023, the Fuller Inquiry began its second phase, looking at safeguarding within mortuaries. The Inquiry was set up following the conviction of David Fuller for sexual assaults on dead women and girls in the mortuaries of the hospitals where he worked.

The Inquiry is naturally focused on preventing future crimes in mortuary settings.

It might be tempting to focus on the fact that extreme and disturbing crimes, like David Fuller’s, are very rare. But at Poppy’s, we believe that they form part of a more widespread problem — mortuaries are hidden away, whether in hospitals or funeral directors, and the work of caring for the dead is not appreciated, understood or sufficiently scrutinised.

This inquiry is an opportunity to change the culture of death care so that it is open and transparent and so that those who work in it are valued and supported. And so that the needs of grieving people, and of those who have died, are truly respected.

Most people will never have cause to visit a mortuary

Too often, mortuaries are in basements with no natural light. Accessible only by a back route, often by the dustbins. They are hidden even to those who work in the same building — very few hospital clinicians will be able to tell you where the mortuary is.

When you go to a mortuary space, it’s often not somewhere you want to spend much time. The room might feel oppressively clinical, with a strong chemical smell.

In some settings, the whole room is refrigerated and the dead are stored in body bags on racks. It feels industrialised and, as anyone who has worked in food distribution will tell you, you can’t spend long in a fridge room without it feeling deeply uncomfortable.

I would be prepared to bet very few NHS Trust CEOs visit their mortuaries on a regular basis. Politicians looking for a photo op stay firmly upstairs in hospitals. In large funeral firms, funeral arrangers support bereaved clients in high street shops, and do not visit the dead people whose funeral they are arranging.

When the dead are stored away from view in spaces that aren’t that pleasant be in and where management do not venture, is it any wonder that there is little scrutiny of mortuary practice?

Safeguarding and basic controls on access to the mortuary are of course vital. But we need a much bigger cultural shift — the care of the dead should be valued as much as the care of the living.

We understand the concept of great care for patients in hospitals, hospices and so on. So too, we need to grasp that there is such a thing as great death care.

What does great death care look like?

At Poppy’s, our mortuary is a beautiful light-filled, airy, converted chapel, which contains a bank of fridges. We maintain the highest standards of infection control, but the room is wood-panelled and feels welcoming.

Our philosophy is that death is natural and care for the dead should be gentle, careful and non-invasive.

We wash people and wrap them in calico, a natural material. We do not use plastics or body bags and we generally do not embalm people, because it is both unnecessary and toxic.

Language matters

The way we talk about people who have died matters too. It affects how we see them, and how they are treated in mortuary spaces.

If the funeral sector continues to use words like ‘disposal’ to describe what happens to someone’s body after they die, it’s easier to see bodies as rubbish to be thrown away than to treat them in a way which honours the person they were in life.

That’s why our Dead Good Words campaign highlights positive alternatives to commonly used words like ‘removal’, ‘deceased’ and ‘viewing’. These alternatives, which we use in our everyday work at Poppy's, express our understanding that people who have died are still people, worthy of care and respect.

Whenever someone joins our team at Poppy’s, understanding the language we use forms part of their training. It underlines and reinforces their practical training on looking after people who have died with gentleness and care.

How do we guard against poor practice?

The mortuary is the centre of our business. All members of the Poppy’s team work regularly in the mortuary, including me as CEO, to keep us connected to the purpose of our work.

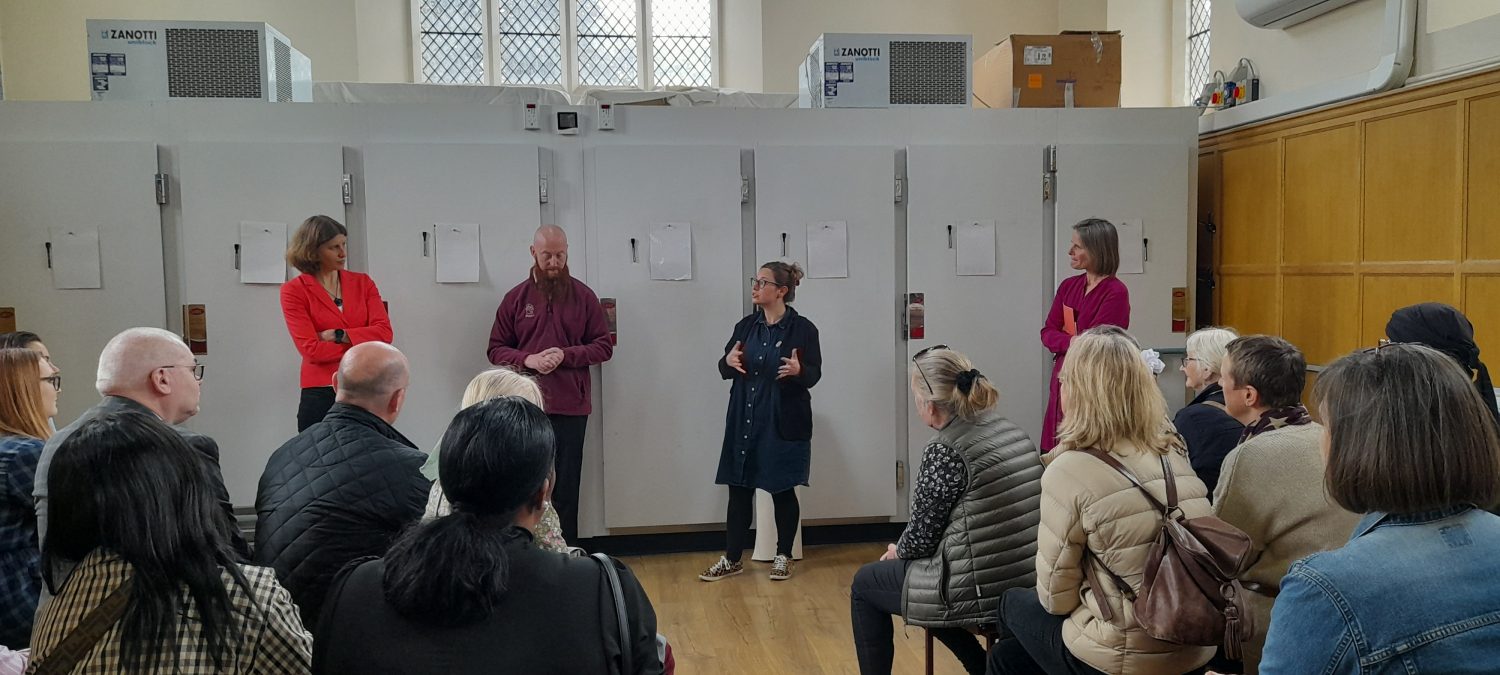

We use the space for training and whole-team meetings — partly because it is the biggest space we have on site, but also because it reminds us of the importance of the care we give to the dead.

We are so proud of our work that we open up the mortuary space, in a safe and well-managed way, as a matter of routine. In May, we welcomed over 40 people from our community to a Mortuary Open Day and answered their questions on death and dying.

We regularly run education sessions for healthcare professionals to give them an insight into what great care looks like after death, as well as in life.

And of course, families and friends often want to come to the mortuary to see where their person is being looked after, or to help dress them or check them in — and we welcome this.

Not everyone will want to come into a mortuary, and that’s OK. But it isn’t OK when institutions consciously hide the mortuary from view. Transparency is the best guard against poor practice in any form.

However, we don’t just want to stop poor practice. We’re aiming higher than that. We want to see outstanding care become the norm. Openness and a willingness to engage with death care could transform all of our experience for the better.

At some point, we will all end up in a mortuary. Wouldn’t it be reassuring to know that we will be cared for in death with the same compassion and gentleness that we see in life?

Read more about why we should open mortuaries to the public and about why great death care matters.

To stay in touch with all the latest news and updates from Poppy's by email, sign up here or contact us if you need help planning a funeral.